Altı ay önce tahminler neydi ?

Arada bir soluklanıp geçmişte yazdıklarımıza bakmalıyız. Ne tür öngörülerde bulunmuşuz, olaylar nasıl cereyan etmiş...Ne kadar…

MUSTAFA SÖNMEZ – Hürriyet Daily News,October/20/2014

The global crisis is behind us, almost six years on. Even though the epicenter was the United States, the European Union also caught fire immediately during the crisis. The U.S. is attempting to stand on its feet after the half-dozen years that have passed, but it is not easy to say the same thing yet for the EU.

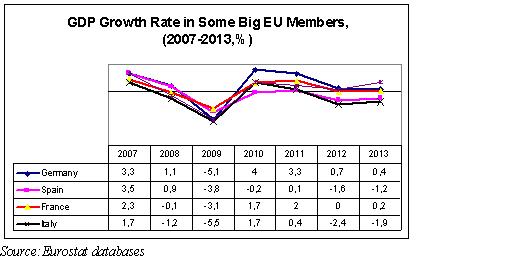

For the 28-member EU, various countries were affected to varying degrees. Some members were heavily wounded, such as Spain and Italy. Germany, on the other hand, which is considered the leader of the union, is in a relatively good situation, and one could even say it grew stronger during the crisis. The United Kingdom is trying to recover with difficulty. However, the big picture tells us that the EU is going through recession and the light at the end of the tunnel has yet to appear.

Loss of jobs

The biggest pain of the crisis was felt by those who lost their jobs. The easiest way to measure the damage of the crisis from country to country is to review the employment losses of countries.

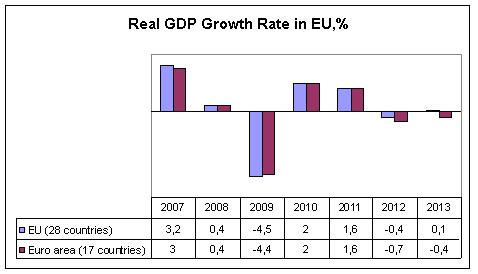

According to the European Statistics Office Eurostat’s data, the EU’s growth rate before the crisis, in 2007, was 3.2 percent. It was rolled back to 0.4 percent first in 2008 when the crisis erupted, but hit the bottom in 2009 when it experienced the biggest shrinkage in its history, dropping 4.5 percent.

Following this shrinkage, in 2010 and in 2011, some relative recoveries were experienced. However, in 2012 the union again experienced a negative growth rate of 0.2 percent. In 2013, a recovery of 0.1 percent was recorded from there. The expectations for 2014 were not pleasant either.

While six years have passed since the global crisis, economic troubles varied from one country to the other. Mediterranean countries, which had difficulty in harmonizing with the transfer to the joint currency, the euro, after 2000, were hit the most by the crisis. Greece experienced the heaviest blow while Spain, Portugal and Italy also received heavy blows. While Germany suffered minor scars because of its export capacity and its current account surplus, the U.K. was fiercely shaken by the crisis but is trying to recover rapidly.

In Europe, the most direct impact of the crisis is on employment. Before the crisis reached its peak, in the last quarter of 2008, the total number of employed in the EU was 219 million. In the second quarter of 2014, however, this number dropped to 214 million, meaning that roughly 5 million people lost their jobs in the global crisis.

No doubt, some of the 28 members experienced major losses in employment; some, though, were able to increase their employment rates. The total losses in the losing countries amounted to 8.9 million, while the winners created around 3.9 million jobs, giving a balance of around 5 million fewer jobs.

The losers

Spain led those that lost the most. Its economy has shrunk four times in five years since 2009; while it had 20.5 million employed at the end of 2008, this figure dropped to 17.2 million at the second quarter of 2014; the loss is an unbelievable 3.2 million. In other words, 3.2 million people lost their jobs in Spain.

When the global crisis came, 4.5 million people were working in Greece. Almost 30 in 100 people lost their jobs in the crisis, and employment went down 1 million to 3.5 million.

In Italy where the crisis also hit heavily, the loss in total employment – which was 23 million – fell 1.2 million. Portugal, meanwhile, suffered 560,000 job losses during the crisis.

While Romania, the Netherlands and Bulgaria constitute the other major countries that experienced losses in employment, Iceland, southern Cyprus, Croatia, Estonia and Slovakia were countries that survived the crisis with small scars.

The winners

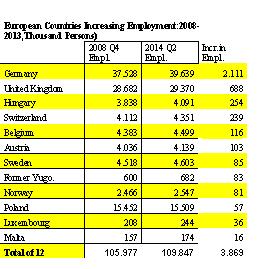

The 11 European countries which increased their employment rather than experiencing losses created 3.9 million jobs, ultimately giving employment to around 110 million.

Germany led this group while distinguishing itself markedly from other countries. This country, after going through a deep shrinkage in 2009 amounting to 5 percent, started hovering at growth rates of 4 and 3 percent in subsequent years. Its growth in the following years followed a horizontal course.

In Germany, the number employed in the last quarter of 2008 was 37.5 million. This figure was 39.6 million in mid-2014. This means an increase of nearly 2.1 million in employment during the crisis years.

Following Germany, it was the U.K. that increased its employment with 734,000 jobs. Also Hungary, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria and Sweden were able to increase their employment rates.

And Turkey

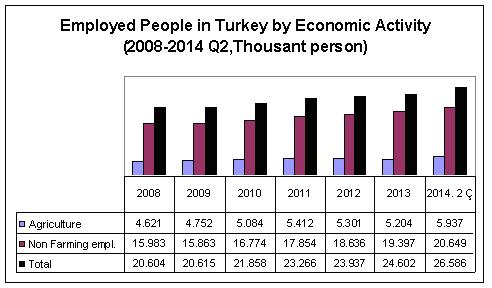

In contrast with the countries in Europe which lost a net 5 million jobs during the global crisis years, EU candidate country Turkey presented a very different profile in terms of employment. During the period in question, Turkey increased its agricultural employment by 1.2 million and its non-agricultural employment by 3.4 million. Even though its non-agricultural employment decreased during the 2009 crisis, it rapidly increased in the subsequent two years. With annual growth of approximately 9 percent in 2010 and 2011, the number of non-agricultural employed neared 18 million.

Despite the growth rate of 2 percent in 2012 and 4 percent in 2013, it was interesting that the rapid increase of employment continued. As of mid-2014, total employment has reached 26.5 million. While almost 6 million of these jobs are in the agricultural sector, 20.5 million are non-agricultural.

Nonetheless, Turkey’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in July 2014 was 10.4 percent; its non-agricultural unemployment rate is 12.5 percent, meaning its unemployment figure has exceeded 3 million.

Nonetheless, Turkey’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in July 2014 was 10.4 percent; its non-agricultural unemployment rate is 12.5 percent, meaning its unemployment figure has exceeded 3 million.

Also, the quality of the employment that seems to have been created in Turkey should be taken into consideration. Even though numerous non-agricultural jobs seem to have been created, their low-paying and low-skilled nature are conspicuous. Labor-intensive industries such as textile and food, as well as construction, tourism and urban services are the main employment fields. An employment profile with low added-value and low productivity constitute the other side of the coin.