How foreign investors force Ankara to toe the line (Al-Monitor.June 11 2018)

ARTICLE SUMMARY With nearly $700 billion in various assets in Turkey, foreign investors represent a…

MUSTAFA SÖNMEZ – Hürriyet Daily News/ December/01/2014

As the year nears a close, one of the constants on Turkey’s agenda is the question of the minimum wage and pay rises for civil servants.

While the minimum wage is determined by a commission that meets in December to decide the twice-a-year adjustment, civil servants’ wages and pensions are decided again in the month of December when the annual central budget comes up for discussion in Parliament.

The segment of wage earners, who total 17.2 million, and the retired, who number in excess of 10 million, have long complained about not being able to participate adequately in this critical decision-making process. Even though it looks like a constitutional right, among the total number of wage-earners, only 1 million of them are members of a union and can negotiate their salaries through collective bargaining. Civil servants are organized under different unions but laws do not allow them to stage a strike. Workers’ unions, on the other hand, have several obstacles to overcome to recruit members, including several thresholds. Also, high unemployment and practices that do not protect workers keep them away from trade unions.

The minimum wage has an “indicator” characteristic that concerns general fees and the level of salary. It gains importance, however, because it is used as a measure in several criteria.

The unions for workers and civil servants, justifiably, complain that these decisions which are extremely important for them are imposed upon them and that they are written in government programs before they are even negotiated. For example, the page 69 of the 2015 program published in the Official Gazette on Nov. 1 announced that the “minimum wage will be raised at a rate of 3 percent in January and July 2015.”

In the 2015 program, pay rises for the retired and civil servants were also outlined as follows:

“Pensions are slated to be raised according to the previous six-month inflation estimate, 3.45 percent and 3.63 percent in January and July, respectively. According to the clauses of collective contracts signed with civil servants, the wages of civil servants and pensioners are slated to be raised at a rate of 3 percent in January 2015 and with the inflation difference expected to total 0.63 percent [in January] and 3.63 percent in July.”

These expressions are enough to make trade unions angry. “What is the point of having commissions meet and forming trade unions?” they frequently complain.

As a matter of fact, the minimum wage should be discussed and decided within the framework of the Minimum Wage Commission. Even though this commission is dominated by government, bureaucracy and employers’ unions, trade unions still criticize the fact that the minimum wage is announced without being decided according to rules.

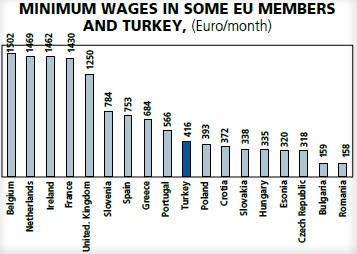

EU comparison

The minimum wage has been set at 5.5 and 5.3 percent in 2014 with a net of 846 Turkish Liras for the first half of the year and 891 liras net for the second half of the year. If what has been planned is put into practice, then the net minimum wage in the first half of 2015 will be 918 liras, rising to 946 liras in the year’s second half. When converted into euros at the average exchange rate for November, the wage will equal 330 euros net.

Eurostat said the minimum wage in 2013 in Turkey was 416 euros. This is only 28 percent of the minimum wage in countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Ireland.

Eurostat said the minimum wage in 2013 in Turkey was 416 euros. This is only 28 percent of the minimum wage in countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Ireland.

The Eurostat data show that in many Eastern European countries, the minimum wage is lower than Turkey. According to 2013 data, the lowest minimum wage is in Romania and Bulgaria at 160 euros, just 38 percent of Turkey’s. However, the 416 euros of minimum wage for Turkey stands for the gross minimum wage. When insurance premiums and tax cuts are deducted from this gross figure, then in 2013, the minimum wage earner was left with just 790 liras in pocket, or 312 euros according to the average exchange rate of 2013.

In Turkey, there are officially almost 3 million unemployed, and there are 2.5 million more unemployed but they are not counted among the unemployed because they do not meet ILO norms. The number of those who do not even have an income equaling the minimum wage is closing in on 6 million. Add to this the housewives who total nearly 11 million and who do not earn anything by doing housework. At a minimum, there are also 2.5 million illegal, unregistered and non-insured workers.

Taking share from growth

The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) government has boasted that it has raised the minimum wage – together with all salaries – above the level of inflation since it came to power in 2003.

Figures seem to confirm this. However, when one mentions inflation, the first objection is the question, “which inflation?” One reason is that the consumer inflation declared is an average and does not take into consideration the relatively higher inflation that salary-wage earners experience. This is the first objection to this. Raises should be made according to calculations based on the inflation of the wage-earner.

Figures seem to confirm this. However, when one mentions inflation, the first objection is the question, “which inflation?” One reason is that the consumer inflation declared is an average and does not take into consideration the relatively higher inflation that salary-wage earners experience. This is the first objection to this. Raises should be made according to calculations based on the inflation of the wage-earner.

The second objection concerns whether the increase in welfare provided by economic growth is reflected in salaries and costs.

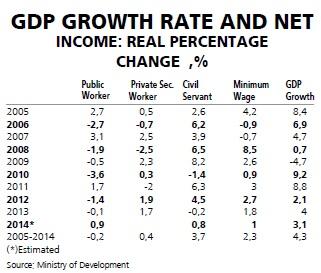

The Development Ministry, on page 134 of the 2015 program, shows the real net income increases of public workers, private sector workers, civil servants and minimum wage earners. While the annual increase in national income with fixed prices in the 2005-2014 period reached 4.3 percent, what happened to the annual income increase of the civil servant, worker and minimum wage earner? Or shall we ask it this way: has the working class been able to have its share from the economic growth?

The number of public workers that are members of a union is almost 500,000 and they are mostly under Türk-İş unions. Their real incomes have, instead of increasing every year, decreased 0.2 percent during the period 2005 and 2013. These public workers, mostly in transportation, municipality, irrigation, energy and mining branches during the AKP period, have become poorer, let alone gaining any share from the increase in national income.

The wages of private sector workers during the 2005-2013 period seem to have risen by an average of just 0.4 percent annually against inflation. However, the national income pie, during the same period, increased 4.3 percent every year. In other words, from the growing pie, workers who are the real producers of the pie have taken almost no share.

The net rise in the incomes of minimum wage earners in these nine years has been 2.3 percent, thus again remaining 2 points behind the annual increase in national income.

The net incomes of civil servants who are 2.5 million look as if they have increased 3.7 percent yearly. As a result, the Development Ministry is saying that the real salary increase of the civil servants is the one closest to the rise in national income.

TÜİK stated that the number of salary/wage earners in Turkey in total employment in 2013 is 17.2 million; this means two-thirds of the employed. A minimum 2.5 million of them are illegal, unregistered workers. The Finance Ministry says the number of those who work for minimum wage is 5 million. The real number of minimum wage earners, when one takes into consideration tax and premium evasion tricks, may come down to 3 million. When you deduct the 2.5 million civil servants, then the biggest segment is private sector workers, the ones who have taken no share from the growth, those who have openly become poorer during AKP years.

The AKP regime seems to have adjusted only the general level of the minimum wage to bring the general wage to a certain level. However, since general wages are not too much higher than minimum wage, it can be said that workers have not benefited from the felicities of growth.