Turkey’s sugar privatization faces bitter opposition (Al Monitor ,March 1, 2018)

ARTICLE SUMMARY The Turkish government’s plan to privatize 14 sugar plants has sparked nationwide protests,…

Mustafa SÖNMEZ – October/26/2013

Madrid, Porto, Lisbon and the Iberian peninsula made me reconsider what Portugal and Spain have and do not have in common with Turkey.

Being Mediterranean is an obvious similarity, but there are also many other historical commonalities. If we look from a point of view based on relations with global capitalism since the 19th century, we can see more similarities with Turkey, especially military dictatorships, their efforts to transition to a parliamentary democracy, as well as other successes and failures.

Turkey’s Kurdish problem and Spain’s Catalonia and Basque problems have many similarities. While Turkey has been waiting at the European Union gate for a long time, Spain and Portugal have become members and also entered the eurozone. However, these two countries are “peripheral,” with destinies that are determined by the Northern European central states, particularly Germany. Today, they have vulnerable economies.

Old empires

Spain and Portugal ruled the world as glorious empires in the same centuries, like the Ottoman Empire. Before the United Kingdom, Germany and France became global powers, these three empires were in a power struggle in the world. Spain and Portugal followed a colonial policy by benefiting from innovations in science and technology, unlike the Ottoman Empire. Their colonial regions were Africa, South Asia and the newly discovered Americas.

The Ottomans, meanwhile, focused on conquest but not colonialism. Its regional administration was different from Europe’s classical feudal regime. The Ottomans applied “the taxational production method,” imposing taxes on the territories that they ruled, while demanding conscripts during war time.

After the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire quickly lost territories, becoming indebted to the German, British and French empires. Resources and markets were also shared, and in the end, only today’s Turkish territory was left.

After the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire quickly lost territories, becoming indebted to the German, British and French empires. Resources and markets were also shared, and in the end, only today’s Turkish territory was left.

Spain and Portugal’s colonial successes were halted in the 18th century as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Germany and Austria grew in Central and Northern Europe by developing capitalism and demanding a share in the colonial scramble. Old colonial and new powers that aimed to transition from competitive capitalism to imperialism fought wars during the 18th and 19th centuries, with Spain and Portugal lagging behind their upstart competition. The Iberian pair, meanwhile, didn’t have bourgeois revolutions that happened in many European countries. While the government was shared between a weak bourgeoisie and pre-capitalist classes, Spain especially fell behind with bloody civil wars. Portugal, meanwhile, was transformed into a peripheral country dominated first by the United Kingdom and then by the United States.

Entering the 20th century, they were two countries that weren’t able to grow. By the end of the power struggles, Spain had fallen under the rule of fascist general Francisco Franco, while Portugal was taken over by rightist economy professor Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, precipitating a 36-year dictatorship.

The counties only found the opportunity to adopt parliamentary democracy in the middle of the 1970s. The European Community, the EU’s predecessor, duly accepted Spain and Portugal, along with Greece, which had also recently exited a military dictatorship, with the aim of expanding the market.

Turkey didn’t have a continuously military dictatorship like Spain and Portugal, but its experience of democracy was no better. It, however, has remained on the substitute’s bench for the EU.

Crisis and street

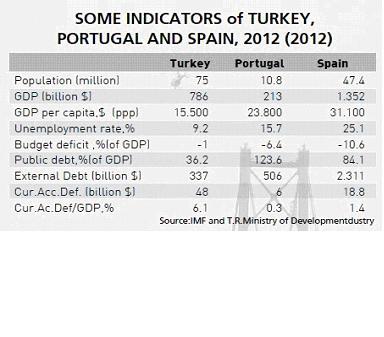

Since 2008, the troika, the trio of the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank and European Commission, has been urging Spain and Portugal, which have big public debts, to discipline their budgets; the trio have imposed sanctions, but the measures have yet to bear fruit. Despite all the austerity measures and privatizations, the budget deficit/national income has not fallen below 6-7 percent in Spain and Portugal. (It is 1-2 percent in Turkey.)

Both countries have high public debts. Spain’s public debts make up 85 percent of its national income, while the rate in Portugal is 125 percent, but only around 40 percent in Turkey. As such, they can borrow loans from the markets only at high interest rates, meaning they are dependent on the troika. After they adopted the euro, they lost their ability to devaluate their own currencies to raise competitiveness, meaning it has been difficult for them to export in the “euro climate.”

Inefficient formulas

Spain and Portugal have been very slow at displaying the progress demanded by the troika. The Iberians haven’t been very successful at getting the expected results from the aid, which Turkey applied during the 2001 economic crisis despite heavy economic and political costs.

Turkey’s situation at the time, however, was quite different. At the beginning of the 2000s, Turkey had an available global market that enabled it to exit the crisis through exports and the devaluation of the Turkish Lira. Also, workers were disorganized and could be threatened with hunger, meaning it wasn’t difficult to get results from the IMF aid. The deputy prime minister of that period, Kemal Derviş, a partner of the IMF, was declared something akin to a hero!

Spain and Portugal are vulnerable in the public sectors, while Turkey has a current account deficit problem and its private sector is seriously indebted. At the same time, Turkey suffers heavily from vulnerability because of a dependency on foreign source inputs.

What’s going to happen?

Can the EU central countries, particularly Germany, keep alive the eurozone with the troubled Iberian countries? Could those countries say they want their national currencies back? My impression is that neither Spain nor Portugal intends to abandon EU membership, but they are in crisis; they have been posting losses for five years after the previous 20-25 years of the EU adventure brought them greater success.

Now, however, they are suffering from debt, rises in unemployment, and young people are especially worried about the future, although they have no plan B apart from the EU.

Ultimately, they would prefer Germany and its chancellor, Angela Merkel, to think about the situation, instead of them; as for Turkey, it doesn’t have such an option. It has to handle its vulnerability by itself, otherwise it will fall into the hands of the IMF again.