Is Turkey’s export-driven growth sustainable?(Al Monitor, September 10, 2021)

A big uptick in exports was a major driver of the Turkish economy’s 21.7% growth…

MUSTAFA SÖNMEZ – October 5, 2014, Hürriyet D.N.

The United States’ Federal Reserve (FED) will cut its bond-buying program as part of plans to end a program that served to support its country’s economy since the global crisis and will slowly increase interest rates.

Following this message from the FED, the capital outflow from “emerging countries” has caused significant losses in local currencies in the past 16 months.

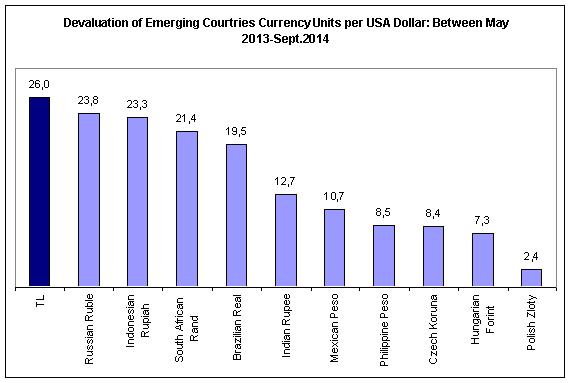

The Turkish Lira leads in this process. The dollar which was 1.82 liras in May 2013 went up to 2.28 liras on Sept. 30, 2014. Thus the lira lost 26 percent against the dollar. In the period in question, the month that the lira lost the most was January 2014, and when the lira lost nearly 7.5 percent against the dollar, the Central Bank opted for shock increases in interest rates.

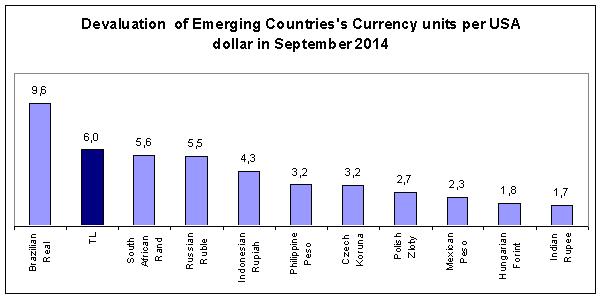

September 2014, on the other hand, has been the second month after January that the lira lost the most. A dollar, which started the first working day of September at 2.16 liras closed the month at 2.28 liras. This performance, which means a monthly loss of 6 percent, means Turkey lost the second most among emerging countries or developing countries in September.

According to the IMF database, the emerging country whose currency was devalued the most in September was Brazil. The Brazilian Real lost 9.6 percent of its value against the dollar in September.

Hot on the heels of Brazil and Turkey, which occupied the top slots in devaluation against the dollar in September, the South African Rand and the Russian Ruble lost 5.6 percent and 5.5 percent over the month, respectively. The currency that lost the least among emerging countries in September was the Indian Rupee at 1.7 percent. The Czech, Polish and Hungarian currencies lost between 1.8 percent and 3.2 percent while it was quite remarkable that the Mexican Peso lost only 2.3 percent this September.

Most fragile in 16 months

The Turkish Lira, with its 4.6 percent loss of value in September, has devalued the most in terms of emerging countries since May 2013. Its devaluation in 16 months has reached 26 percent. A similar erosion has been observed in Russia’s national currency, as the country has been hurt by an embargo.

The 16-month devaluation of the ruble has reached 23.8 percent, with the erosion in the currencies of Indonesia and South Africa following it. The real’s erosion over the past 16 months was 19.5 percent. The least devaluation during that period was seen in European emerging countries. The devaluation in the Polish, Hungarian and Czech currencies in this 16-month period stayed in the corridor between 2.5 and 8.4 percent.

The adventure of the lira

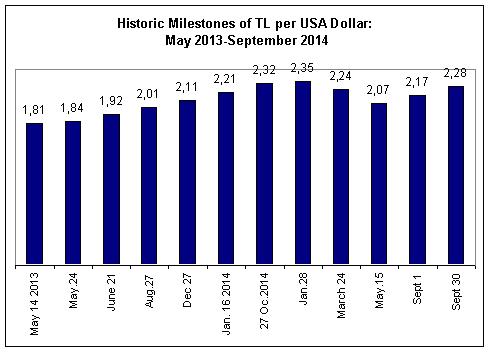

While the lira was in the 1.80 TL/$ corridor in mid-2013, there was a nearly 4 percent loss in June, taking it up into the 1.90 lira corridor. The lira could not recover in the following months, even hitting 2.00 liras in August. Capital outflow occurred from the country, the political risk of which rose with the graft operation of Dec. 17 and Dec. 25, 2013, while new inflow also dropped. Therefore, at the end of 2013, the value of the lira against the dollar jumped into the 2.10 corridor.

With the political risk added to the economic risk, the dollar hit 2.20 liras on Jan. 16, 2014, and went up to 2.35 on Jan. 28, showing signs of a further upward trend. On that date, in a belated action according to several experts, the Central Bank intervened with interest rates and increased the weekly repo interest rate from 4.5 to 10 percent – in other words, with a shock increase of 5.5 points, intervening in the devaluation.

Following this severe intervention with interest rates and following the local elections on March 30, the political risk perception decreased, and the dollar went down to 2.07 in mid-May. However, there were presidential elections on the agenda and the hot clashes in the region were deepening. With the effect of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) attack in Iraq, Turkey’s geopolitical risk increased. With this perception, the price of the dollar in the following months went up from the 2.10 lira corridor to 2.20 liras, completing its climb to 2.28 liras by the end of September.

In the face of the devaluation of the lira, the Central Bank, despite all the pressure, did not reduce interest rates openly. However, it increased the number of dollars it sold to the market from 10 million to 40 million in the last week of September. It also restricted the liquidity amount it was supplying to the market to 8.25 percent and allowed the overnight rates to go up to 10.9 percent on Friday. In other words, it increased interest rates not in an official way, but via an indirect path.

Short-term loans

The dollar exchange rate is expected to more negatively affect firms that have short-term loans and banks. Even though the bank valued that short-term loans at the end of July at $130.2 billion, the total amount of loans to be returned within 12 months exceed $167 billion. Out of the short-term $167.1 billion loans stock, the portion of $23.4 billion belongs to the loans of local branches of banks, while those of private sector companies belong their overseas branches and subsidiaries.

The public sector has a share of 15 percent in the total loan stock, the bank 1.2 percent and the private sector 83.8 percent.

The biggest portion of the loans that are due within the next 12 months belong to private banks at $85 billion. However, public banks such as Ziraat and Halk also have almost $20 billion in short-term loans.

Firms, namely the real sector, have nearly $49 billion of loans squeezed into 12 months and a significant amount of them are import loans. Apart from public banks, the Treasury has liabilities associated with Eurobonds at nearly $8 billion, also within the next 12 months.

External debts constitute an important vulnerability. There is a concern that the dollar exchange rate which will probably jump to 2.30 liras threshold soon will result in serious fractures both in banking and in the real sector. In this case, the suggestion is that those firms that have major exchange rate expenses in their 2013 balances will become more fragile and start queueing up to be saved and that the bad debts of banks will increase.